Singing River Contact Tracing Efforts and Community Education with COVID-19

By: James C. Noblin, BSIE, Stephanie Holder, LPN, Daralyn A. Boudreaux, RN, MSN, CIC, CPHQ, Sonya F. Barber, RN, BSN, MHA, HACP, Sarah Duffey, MBA, Okechukwu Ekenna, MD, MPH, Ijlal Babar, MD, FCCP, FAASM, Lee Bond

Jackson County, Mississippi, March-June 2020 — COVID-19, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, is an infectious disease that surfaced in late 2019. This virus is typically associated with symptoms such as cough, shortness of breath or difficulty breathing, fever, chills, muscle pain, sore throat, and loss of taste or smell. This virus is more problematic in individuals with underlying medical conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, and cancer.

COVID-19’s primary pathway of transmission is through droplets of saliva from an infected person. The three primary opportunities for transmission of the virus are household contacts, large gatherings, and healthcare facilities. In the cases we have followed, many more people became infected from household contacts, friends, and acquaintances than from the other transmission opportunities. The best ways to attempt to avoid COVID19 are to wash your hands often with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, avoid touching your eyes, nose, and mouth when in public or with unwashed hands, practice physical social distancing of at least six feet apart, wear a facial covering or mask, and avoid large groups and gatherings.

Singing River Health System has taken multiple measures to help educate and protect the surrounding community during this epidemic. Singing River is owned and operated as a nonprofit Community Health System of Jackson County, Mississippi. The health system consists of a total of 571 beds across the facilities. This article’s intent is to show the process of contact tracing and community education within a community health system.

COMMUNITY EDUCATION

On March 5th, when the likelihood of a local outbreak became eminent, the administration of Singing River dedicated an hour per day to COVID-19 strategy meetings that focused on the plan moving forward. These meetings were held seven days a week and consisted of over 70 participants and over 60 unique initiatives. One of the first notable initiatives that surfaced from the meetings was a COVID-19 hotline. On March 10th, Singing River Health System implemented a 24 hours a day, 7 days a week hotline. This line fielded over 400 calls per day during peak season. The main purpose of the hotline was to allow providers to talk to patients and guide them in the right direction for screening, testing, hospitalization, and if needed, treatment. This allowed the patients that only needed questions answered to stay away from the hospitals and emergency rooms which helped minimize congestion in these areas.

The Pulmonary Critical Care Team, Infectious Disease Department, Hospitalists, Nursing, and Administration at Singing River Health System decided at the beginning of the outbreak to designate one of their two hospitals as the main location for COVID-19 patients to provide the benefits of a cohort. This allowed for the facility to be quickly adapted to be able to accept infected patients without significantly hindering the normal workflow of the hospital. The engineering team on staff was able to convert 24 beds into negative pressure rooms and 16 medical surgical beds into complete negative pressure rooms, beyond the smaller number of existing and normally used negative pressure rooms. The reasoning for these negative pressure rooms is to help prevent airborne microorganisms from escaping the room and infecting others. This transformation of additional rooms allowed for a smooth transition and extra assurance to employees, patients, and medical staff due to the increased protection. With only one facility housing COVID-19 patients, it also made it much easier to efficiently educate the hospital staff about proper personal protective equipment (PPE) utilization and conservation which proved very beneficial due to the PPE shortage throughout the country.

Singing River Health System made a continual, conscious effort to educate the public about the ongoing epidemic. Biweekly calls were made to local nursing homes to support their needs and educate their staff. Daily updates were shared with community leaders. Weekly calls with other facilities in the region and a nearby Air Force base were made to educate on best practices, treatments, and other COVID-19 specific needs. The leadership team of Singing River conducted interviews, workshops, and conferences to educate the public through civic organizations, businesses, schools, and churches on the importance of hygiene, physical social distancing, staying at home alone to reduce the spread of the virus, and the importance of safely reopening the community.

SOCIAL MEDIA

Singing River also used social media to help spread the details of COVID-19 and curtail the virus with daily Facebook live videos and robust website updates. During the medical battle against COVID-19, Singing River’s Marketing and Communications Team continuously updated the system website which grew into ten dedicated COVID-19 pages. These pages were filled with information and resources regarding the system’s statistics which were presented in a statement released by the CEO daily. These updates regarded visitation policies at the system’s facilities, frequently asked questions to keep the community informed and calm, and “Singing River Strong” messages.

“Singing River Strong” is a motto that was adopted throughout the pandemic. These materials helped the Marketing and Communications Team build additional content for social media pages, as this platform was the most successful channel to reach as many people as possible within the community. This also gave the team the ability to keep the public up to date on the ever-changing situation of COVID-19. Every day, Singing River reported the total number of cases confirmed within the system, tests collected, results received, and how many people were in an inpatient or outpatient setting. Singing River was the only health care system in the region that reported these statistics, which built credibility about the system’s transparency within the community.

After an influx of support for the updates and videos, Singing River grew into providing daily Facebook Live videos which combined the statistical updates and commentary from leading health care professionals relaying their experiences from the frontlines against COVID-19. Singing River’s Facebook page increased 1393% in user engagement in 85 days due to the content regarding the virus.

The most successful marketing campaigns launched during the pandemic were informative stories regarding the virus. “Stop the Spread, Call Ahead” urged those with symptoms to call the 24/7 hotline to be screened before visiting any facility that could put others at risk. “Facts, Not Fears” helped myth bust and explain the topics being discussed in the media regarding COVID-19 and the “Singing River Hero” stories of frontline healthcare workers around the health system and the yard signs that were placed in each team members’ front yards by volunteers. These marketing campaigns paired with the continual informing of the public with COVID-19 statistics allowed Singing River to have one of the top healthcare pages in the state of Mississippi.

TELEHEALTH

When Singing River admitted its first COVID-19 positive patient on March 9th, the health system had to adopt a limited visitor policy. Due to the visitor limitations, there needed to be some other method of communication between providers, patients, and family members. To try to provide continuity of care, telehealth technology was quickly deployed. Telehealth allows providers to communicate and support patients via video conferencing and store-and-forward imaging. Within the first 60 days of using this mode of communication, 97% of the health system’s providers were conducting televisits, and over 10,000 visits were conducted using this medium. The platform is still being used today, and the functionality of the software has been extended to allow families to communicate with their loved ones who are being treated in the hospital. Due to the unforeseen circumstances of the virus, Singing River was able to implement telehealth technology on a significantly quicker timeline than expected.

CONTACT TRACING EFFORTS

One of the most notable products derived from the daily meetings, and largely the primary impetus for sharing this article, is that just a short time into the outbreak, a group of 15 staff members volunteered to formally aid patients in the navigation process following a positive COVID-19 test. During the process of navigating patients that were positive and dividing responsibilities for inpatient and outpatient positive patients, Singing River Health System decided to extend the patient navigator role to include elements of contact tracing. Typical contract tracing tasks such as supporting patients and warning contacts of exposure to stop chains of transmission were added to the navigator role. As the pandemic expanded, more navigators were assigned and the role became expanded as well, to include extensive contact tracing. The State Health Department had limited resources and was unable to respond quickly to every positive patient due to the magnitude of the outbreak. The patient navigator role transformed into a culmination of tasks that involved contact tracing, epidemiology, navigating, and educating. Much time was spent educating patients and their families on isolation and identification of contacts.

Contact tracing can be consuming of both resources and time. Contact tracing members assisted infected patients in recalling who they may have been in close contact with that may have become infected. The potentially infected parties are informed of possible exposure, provided education, and encouraged to follow the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) guidelines to quarantine for at least 14 days to keep the surrounding community safe. The potentially infected parties receive information and support to understand their potential risk and how they can spread the infection to others around them. Throughout this process, the contact tracer remains in contact with the known infected individual to ensure that he or she is staying safe and out of the public. This also allows the infected individual to voice any questions or concerns to a knowledgeable medical professional. As more and more individuals are becoming infected and supplies are running scarce, it shows the true importance of reducing potential infections through contact tracing.

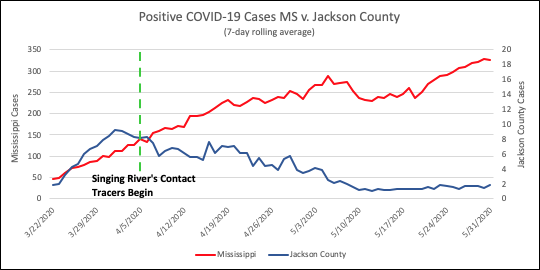

As Singing River Health System’s contact tracers continued their efforts, clusters were identified within the surrounding communities. Through discussion with an infected patient or household contact, contact tracers could identify public health guidelines were not being followed, and it could be determined that the source of the contagion was either the infected person or the person who had infected them that spread the virus. Singing River was able to share with the community in Jackson County, Mississippi, which areas were becoming hotspots for the virus. This allowed the public to be more careful in these areas to reduce the opportunity for added exposure. Due to the aggressive contact tracing efforts and continual education of the public that Singing River Health System portrayed, there was a notable decline in positive cases moving forward within the county. The decline in positive cases is shown on the following page in Figure 1.

INSTANCES OF CONTACT TRACING

Due to patient privacy practices, the specific identity of the infected individual must remain undisclosed throughout this process. For the denoting of patients in the following cases of contact tracing, the format of A11 will be used. “A” will be used to denote the patient belonging to the family cluster “A.” The subscript numbers will be denoted by event order and transmission order, respectively. For example, A11 belongs to family cluster A that became infected by the first known event as the first infected individual of that family cluster.

In one instance of contact tracing in March, patient B11, not feeling well, came over to patient A11’s home to visit. On the same day, patient C21 came over to patient A11’s home to do housework. The patient not feeling well initially, patient B11, tested positive for COVID-19 on 3/23. Patient A11’s wife and household contact, patient A32, developed symptoms of the virus and tested positive on 3/28. Patient A11 was tested due to patient A32’s positive test and being household contacts. Patient A11 tested positive for COVID-19 on 4/1. Also, on 4/1, patient C21, the friend doing housework, received a positive test result. Patient C21’s son and household contact, patient C42, tested positive for COVID-19 on 4/4.

Patient B11, the original friend not feeling well, received a second positive test result on 4/10, 19 days after the first test result. Unfortunately, patients C21 and A32 both passed away due to complications of the virus. In this case, there were five COVID-19 positive patients, two of which lost their lives to the virus. One patient also had a relapse of symptoms and tested positive for a second time.

Patient F11 is a healthcare professional. This patient traveled by plane to a COVID-19 hotspot to attend a family celebration. Patient F11 tested positive for COVID-19 on 3/25. No other family members of the family cluster “F” developed symptoms or received a positive test result. Patient F11 adhered to CDC guidelines and quarantined for 14 days. After the quarantine concluded, this patient was safe to return to work.

In another case, the manager of a construction crew, patient W11, visited the house of patient X11 on 3/24. On 3/30, patient X11 and the patient’s three children, X22, X23, and X24, started to develop symptoms of COVID-19. Patient X11 quarantined after symptom onset and tested positive on 4/20. Patient W11 received a positive test result on 4/1, but this patient insisted on continuing work after symptom onset. Patients X22, X23, and X24 are considered probable COVID-19 positive patients due to the similar timeline of symptom onset and the sharing of a household with a positive patient, patient X11. This construction crew worked on jobs ranging from New Orleans, Louisiana, to Birmingham, Alabama. Singing River Health System was able to assist patient X11’s family by delivering informational packets and needed supplies to aid the family while the head of the household quarantined with the virus. In this case, there were two positive COVID-19 patients and three probable cases.

Patient H11 was the manager of a gas station. Patient H11 was tested for COVID-19 on 4/4 and continued to work until 4/10, when patient H11 received a positive test result. Patient I11 was an employee of the gas station. This patient felt no symptoms other than headaches. Patient I21, parent and household contact of patient I11, developed symptoms on 4/4. Symptoms worsened, and Patient I21 tested positive on 4/12. Patient I22 was also a household contact of the family cluster “I”. Patient I22 tested positive for the virus on 4/15. Patients I21 and I22 claimed to not have gone anywhere for quite some time. During this timeframe, multiple other employees were out sick. Patient I11, an employee of the gas station and household contact of the “I” family, is considered a probable COVID-19 positive patient due to the household contacts being positive and no test being completed. In this case, there were three positive COVID-19 patients, one probable patient, and potentially multiple other employees that were positive for the virus.

Patients M11 and M12 were household contacts that recently returned from vacation at Walt Disney World. Patient M12 worked in the entertainment industry. Patient N11 also worked in this sector in the same department as patient M12. Patient M12 coughed in a small vicinity of patient N11, precisely onto patient N11 and a shared keyboard. Nearly a week after this occurred, Patient N11 developed symptoms that were first believed by an urgent care facility to be sinus symptoms. After worsening and going to a Primary Care facility, this patient received a positive COVID-19 test on 3/23. Patient M11 also received a positive test result. After the test results, Patient N11, who suffers from asthma, developed worsening symptoms, and was hospitalized for over two weeks.

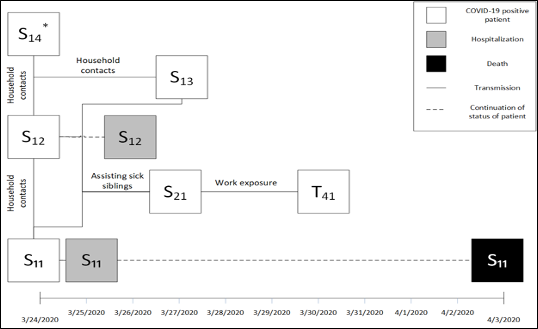

In an instance shown in Figure 2 on the following page, patients S11, S12, S13, and S14 are household contacts. All three patients developed symptoms of the virus in mid-to-late March. A sibling of the symptomatic patients, patient S21, came to assist in taking care of patients S11, S12, and S13. Patients S11 and S12 tested positive for COVID-19 on 3/24. Patient S13 received a positive test result on 3/27. Patient S14 also received a positive test result, but the date of the test result is unknown. Patient S21, the sibling assisting the household, developed symptoms on 3/25 and tested positive for COVID-19 on 3/27. Patient T41 was working directly with patient S21 on the two days prior to patient S21’s positive test. Patient T41 developed symptoms on 3/30 and tested positive for COVID-19 on the same day. In this case, five individuals received positive test results. Unfortunately, one of the five individuals, patient S11, passed away because of the virus.

Patient O11 was a COVID-19 positive patient. Patient O12 was a household contact of patient O11. Patient O12 visited a local assisted-care facility where two employees, patients P21 and Q21, subsequently tested positive. After this exposure, but before symptom onset, patient Q21 attended a family gathering of over 50 people. The evening of the gathering, patient Q21 spent the night at the parents’ home. The following day, patient Q21 and the father, patient Q32, developed symptoms for COVID-19. Without knowledge of the father’s symptoms, patient Q21 sent the children to stay with the parents to prevent obtaining the virus. Patient Q21 tested positive for COVID-19 on 4/1. Days after, patient Q21’s daughter, patient Q44, and patient Q32 tested positive. Patient Q21’s mother, patient Q33, tested positive on 4/10. In summary, a household exposure of COVID-19 was presented to an assisted-care facility where two employees were infected. One of these two employees possibly exposed over 50 individuals at a large family gathering. At least three confirmed COVID-19 positive patients can be linked back to patient Q21.

In an instance of a manual labor workforce that works predominately outside, the crew was thought to have been exposed to a COVID-19 positive patient. Being proactive, the workforce manager insisted that the entire crew be tested for the virus. Out of 26 employees tested, nine employees tested positive for COVID-19 on 6/5.

Through contact tracing, many cases have been documented where patients mistake COVID-19 for a common sinus infection due to the similarities in some symptoms. Patient α11 believed to have a sinus infection. In attempt to treat this, the patient attended an urgent care clinic on 5/27 where patient α11 received an Azithromycin antibiotic, commonly referred to as a Z-Pak. After receiving and taking the antibiotics for multiple days, patient α11 started to feel better and returned to work at a public entity. Over the next week, multiple employees of the entity started to become sick. One employee tested

positive for COVID-19 on 6/5. Patient α11 tested positive on 6/7. Another employee received a positive test result on 6/10. Patient α11’s significant other, patient α22, works for a personal care service. Patient α22 tested positive for COVID-19 on 6/7. In summary, five employees of a public entity tested positive for the virus with large potential of exposure to other individuals. Patient α22 tested positive while working for a personal care service which also had a large potential of exposure to individuals within the community.

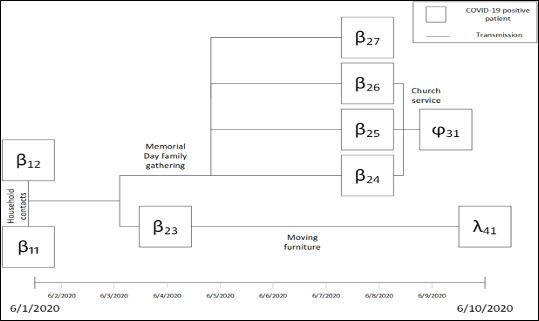

In a case shown below in Figure 3, a member of a traveling manual labor group began to feel sick the week of 5/18. This individual, patient β11, was diagnosed with Walking Pneumonia the same week. On Memorial Day, 5/25, patient β11 attended a family gathering. On 6/1, patient β11, and this patient’s household contact, patient β12, tested positive for COVID-19. On 5/31, patients β24, β25, and β26, who all attended the family gathering, attended a church service. Patients β24, β25, and β26, all received a positive test result on 6/8. At the church service, these three patients exposed patient ϕ31 to COVID-19. Patient ϕ31 tested positive for the virus on 6/9. Patient β27 also attended the Memorial Day gathering and received a positive COVID-19 test result on 6/8. Patient β23 assisted a friend, patient λ41, in moving furniture in a household setting on 6/1. Patient β23 tested positive for the virus on 6/4. Patient λ41 tested positive on 6/10. In summary, 7 family members contracted the virus from a family gathering. There are also 13 probable COVID-19 positive patients involved with the family cluster “β”. Through encounters with friends and acquaintances, two additional individuals tested positive for the virus.

Patient Z11 is an 80-year-old with a home oxygen concentrator (HOC). This patient falls into the age range and pre-existing medical condition categories that COVID-19 strikes harshly. Patient Z11 quarantined for 14 days and was able to make a full recovery. This is an instance of hope for individuals that fall into either of these two categories regarding age or pre-existing medical conditions.

Many other connections were made, allowing the navigators to assist not only the patient but also those who the patient encountered, thus potentially helping to limit the spread of the virus. This process led to community benefit actions of both individualized and mass education which, based on our experience, has been instrumental in helping slow the spread of the virus.

A barrier identified in Singing River’s contact tracing efforts surrounds some patients refusing to communicate with contact tracers due to the thought of being asymptomatic. There has been much debate over asymptomatic transmission. Some experts believe asymptomatic carriers are not a primary culprit for spreading the virus, which is a conclusion that is congruent with Singing River’s contact tracing results. This emphasizes the fact that education should be most focused on avoiding clear sources of transmission. In addition, it was learned throughout the process that many people have symptoms but ignore them or are relatively unaware of the symptom. Examples of this could be an initial or brief episode of cough, fever, or fatigue. Our investigation supports multiple occasions where patients stated they were “asymptomatic” but upon further discussion reported a brief episode of at least one symptom. Whether symptomatic or not, contact tracing and community education helped reduce the spread of COVID-19 within the Jackson County community.

CULMINATION OF COMMUNITY EDUCATION AND CONTACT TRACING

Continual education of COVID-19 to the community in conjunction with vigorous contact tracing was able to decrease the amount of positive cases per day. Singing River, being a small, community health system, was able to alleviate certain tasks of healthcare professionals to allow opportunity for workers to be a part of a greater change. Some healthcare workers that would not have had a direct impact on COVID-19 outcomes were able to directly impact the pandemic through their efforts. These professionals were able to serve as contact tracers and continually educate the public on the specifics of the virus which allowed the people of the county to go forth into the public with knowledge to protect themselves.

Due to the unprecedented times of a worldwide pandemic, Singing River Health System was forced to take drastic action to ensure the health of the community. While the entire process started with the first line care of the patient, the combination of leadership meetings, navigation, contact tracing, and community education proved to be paramount in gaining control of COVID-19.

Acknowledgments

The patients outlined in this article; Singing River Health System’s health care personnel that cared for the patients; Singing River’s infection prevention team; Singing River’s COVID-19 contact tracing/navigator team.

Corresponding author: Sonya F. Barber, [email protected], 228-809-2383.

1Singing River Health System; 2Singing River’s infection prevention team; 3Singing River’s COVID-19 contact tracing/navigator team.

References

- Case Definition – Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19). Health.Gov. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/coronavirus/docs/2019_case_definition.pdf. Published May 11, 2020. Accessed May 28, 2020.

- Contact Tracing: Part of a Multipronged Approach to Fight the COVID-19 Pandemic. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/php/principles-contact-tracing.html. Published April 29, 2020. Accessed May 28, 2020.

- Coronavirus. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1. Accessed May 28, 2020.

- Hospital Isolation Rooms. Hospital Isolation Rooms | Michigan Medicine. https://www.uofmhealth.org/health-library/abo4381. Accessed May 28, 2020.

- Lee A. ‘Absolutely maddening.’ Unmasked MS residents are spreading COVID-19, health officer says. Sun Herald. https://www.sunherald.com/news/coronavirus/article243634762.html?utm_source=pushly. Accessed June 26, 2020.

- Medical Care for the MS Gulf Coast. Singing River Health System. https://singingriverhealthsystem.com/. Published January 28, 2020. Accessed June 26, 2020.

- Mississippi State Department of Health. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Coronavirus COVID-19 – Mississippi State Department of Health. https://msdh.ms.gov/msdhsite/_static/14,0,420.html. Accessed May 28, 2020.

- Rose J. Coronavirus Testing Machines Are Latest Bottleneck In Troubled Supply Chain. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2020/05/28/863558750/coronavirus-testing-machines-are-latest-bottleneck-in-troubled-supply-chain. Published May 28, 2020. Accessed June 26, 2020.

- Simmons-Duffin S, Stein R. CDC Director: Very Aggressive Contact Tracing Needed For U.S. To Return To Normal. WLRN. https://www.wlrn.org/post/cdc-director-very-aggressive-contact-tracing-needed-us-return-normal#stream/0. Accessed May 28, 2020.

- Telehealth Programs. Official web site of the U.S. Health Resources & Services Administration. https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/telehealth. Published June 1, 2020. Accessed June 26, 2020.

- William Feuer NH-D. Asymptomatic spread of coronavirus is ‘very rare,’ WHO says. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/06/08/asymptomatic-coronavirus-patients-arent-spreading-new-infections-who-says.html. Published June 10, 2020. Accessed June 30, 2020.